Bandit Algorithms for Website Optimization

by Kwanghee Choi

Overview & Disclaimer

This is a summary of the book Bandit Algorithms for Website Optimization by John Myles White. This book is quite short, but it doesn’t mean that it hasn’t got content. The author summarizes useful ideas and insights in kind words for people outside of the field. Note that every image in this post are from the book itself. Special thanks to Tampines Regional Library, where I found this gem.

1. Two Characters: Exploration and Exploitation

- Need to balance experimentation (exploration, learning new ideas, gathering data) with profit-maximization (exploitation, taking advantage of the best of old ideas, acting on that data).

2. Why Use Multiarmed Bandit Algorithms?

- Examples of measurable achievements: Traffic, Conversions, Sales, CTRs

- Reward: Measure of success

- Arms: List of potential changes

- Explaining standard A/B testing as an exploration - exploitation tradeoff

- Short period of pure exploration (Assigning equal numbers of users to A/B)

- Long period of pure exploitation (Send all of the users to successful option)

- Why A/B testing might be a bad strategy?

- Abrupt transition

- Wastes resources exploring inferior options

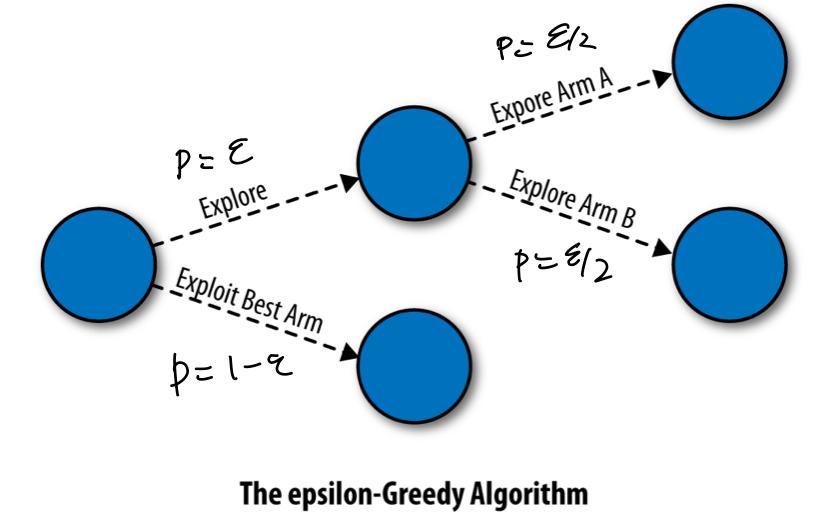

3. The $\epsilon$-Greedy Algorithm

- Tries to be fair to the two opposite goals of exploration & exploitation

- If $\epsilon = 0$: Pure exploitation, $\epsilon = 1$: Pure exploration

- Problem of fixed $\epsilon$

- May need more exploration at the start, may need more exploitation after some time.

- Explores arms completely at random without any concern about their merits.

- Computing average $A_n$ of rewards $r_1, r_2, …, r_n$ online

- Average: $A_n = \frac {1} {n} \cdot r_n + \frac {n-1} {n} \cdot A_{n-1}$

- Weighted Average: $A_n = (1-\alpha) \cdot r_n + {\alpha} \cdot A_{n-1}$ with decay factor $\alpha$

4. Debugging Bandit Algorithms

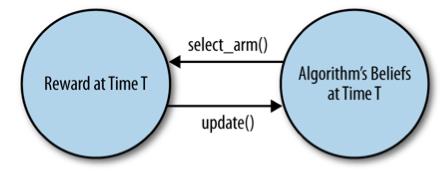

- Bandit algorithms are not black-box functions.

- Bandit algorithms have to actively select which data it should acquire (Active Learning) and analyze that data at real time (Online Learning).

- Bandit data and bandit analysis are inseparable. “Feedback cycle.”

- Use Monte Carlo simulation to provide simulated data in real-time.

- Analyzing results

- Tracking the probability of choosing the best arm, as both bandit algorithms and rewards are probabilistic.

- Tracking the average reward at each point in time.

- Tracking the cumulative reward at each point in time, to look at the bigger picture of the lifetime performance.

5. The Softmax Algorithm

- Problem of fixed $\epsilon$ revisited

- If the difference in rewards between two arms is small, more exploration is needed, and vice versa.

- Never get past the intrinsic errors caused by the purely random exploration strategy.

- Set the probability of choosing arm $A$ with accumulative reward $r_A$ as …

- $p_A = \dfrac {e^{r_A / \tau}} {e^{r_A / \tau} + e^{r_B/ \tau + …}}$

- Temperature parameter $\tau$ shifts the behavior along a continuum between pure exploration $(\tau=\infty)$ and exploitation $(\tau=0)$.

- Negative rewards are okay thanks to exponential rescaling.

- Annealing: Encouraging to explore less over time by slowly decreasing $\tau$.

6. UCB - The Upper Confidence Bound Algorithm

- Problems of softmax algorithms

- Only pay attention on how much reward they’ve gotten from the arms.

- Gullible: easily misled by a few negative experiences, as the algorithm do not keep track of how much they know about the arms (how much confident).

- UCBs avoid being gullible by keeping track of confidence in assessments of the estimated values of all the arms.

- UCBs doesn’t use randomness.

- UCBs doesn’t have any free parameters.

- UCB1 (one of the variants of UCBs) chooses arm $i$ with accumulative rewards $r_i$, bonus $b_i$, and number of times $n_i$ as …

- $i = \underset{i} {argmax} (r_i + b_i)$

- $b_i = \sqrt{ \dfrac{2 \ln (\sum_j {n_j})} {n_i} }$ where $n_i > 0$ and $b_i=\infty$ where $n_i = 0$.

- Cold start is prevented by $b_i=\infty$

- UCBs are explicitly curious algorithms. Curiousness are implemented with bonus $b_i$, where $b_i$ gets bigger when $n_i$ is too small. So, we will occasionally visit the worst of the arms.

- Comparing bandit algorithms side-by-side

- UCB1 is much noisier than $\epsilon$-Greedy or Softmax.

- $\epsilon$-Greedy doesn’t converge as quickly as Softmax.

- UCB1 takes a while to catch up with Softmax.

- UCB1 finds the best arm quickly, but the backpedaling it does causes it to underperform the Softmax.

7. Bandits in the Real World: Complexity and Complications

- A/A Testing

- Testing of bandit algorithms itself

- Estimation of the actual variability in real-time data.

- Running concurrent experiments

- May have strange interactions between experiments (ex. different logos and fonts)

- Continuous experimentation vs. Periodic testing

- Bandit algorithms look much better than A/B testing when you are willing to let them run for a very long time.

- Metrics of Success

- Optimizing short-term CTR may destroy long-term retainability.

- Rescaling metrics into 0-1 space helps algorithms to work well.

- Moving worlds

- Arms with changing rewards raise serious problems.

- Average (No parameter to tune) vs. Weighted Average (Flexibility towards moving worlds)

- Contextual Bandits

- May exploit correlations between arms (LinUCB, GLMUCB).

8. Conclusion

- There is no universal bandit algorithm that wil always do the best job. Domain expertise and good judgement will always be necessary.

- There is always a trade-off between exploration & exploitation.

- Initialization of an algorithm matters a lot. Biases may both help or hurt.

- Make sure you explore less over time.

Subscribe via RSS